Graduating with a photography degree from Glasgow School of Art, Miller has become a successful working artist in his own right, creating installations for public spaces, galleries and homes. Like out other speaker this week, Miller also works a lot with found objects and explained how he often thinks in regards to his artwork in terms of entertainers Morecambe and Wise, “One without the other is not going to work”. This way of explaining his thought processes immediately made me feel at ease as he made light of important decision making to suit his plans.

Once finishing his education, Miller went on to work in a disused space with two other artists to show their work and get their styles recognised. This is where he discovered his enjoyment of public interaction whilst they responded to the architecture of the place. He began to take photographs of the reactions of people to everyday scenarios to release this interest. His consideration for the experiences of others seems a lot deeper than he may have let on.

Miller created an installation featuring a basketball which he bounced off the wall until physical evidence of the activity occurred, linking to childhood experiences of playing outside in the same place until damage is apparent. Much of this earlier work seems to have a much more personal concept, highlighting the vulnerability of people as a result of their surroundings.

When considering interactive artwork, Miller also developed a space for people to use. ‘Breakfast Bar’ was intended for people to come and eat together and respond accordingly as they dined within the artwork that he had built.

It is after this that we see Miller’s work becoming more constructive and being made for a purpose as opposed to a concept or idea. Using his skills in woodworking, Miller built a piece of furniture for a group exhibition that held all the papers of the other artists in the gallery, but stood alone as an individual piece.

He explained how part of his learning was about looking at the architecture and on a trip to the Caribbean for a group restoration project he was sure to consider the buildings and structures around the area. The run down hut-like buildings which were run down and unsustainable were in high contrast with newly built petrol stations adorned with bright lights and manmade materials. Miller was keen to bring this contrast of ideas together and to replicate the light of the surrounding buildings.

Miller discussed his graduation from art school and how after he was free to begin his career, he found that he was very unsure of what he really wanted to do. He explained how it was very beneficial to him to assist other artists in terms of networking as well as gaining experience with professionals to see the process of sale, exhibition and making. Miller was also part of many installation crews, which helped him to develop his skills for the work he now builds and displays. When creating his own work, he was sure to point out the importance of model making on smaller scales or with cheaper materials to allow the client or gallery to get a sense of his ambitions for the piece. Miller explained how working with models helps him to show the viewer how the space will be realised and to realise the scales for himself.

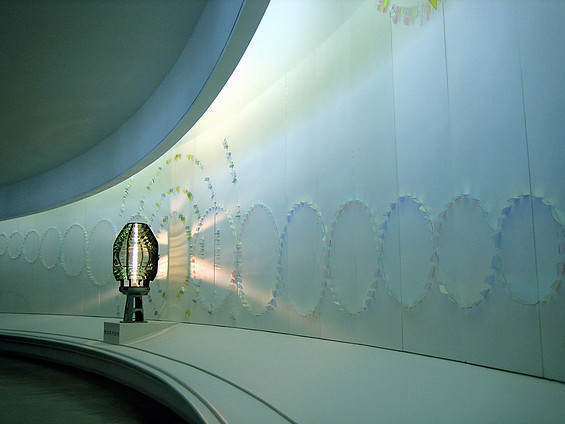

When winning a commission for MIMA it became evident to Miller that it isn’t always the most important aspect of the work to fill up the space, but to consider how his piece will be used, as they are so often interactive. He is able to breathe life into a space by incorporating new and exciting structures within it.

As well as all of his work with structures, Miller still makes time for photography where he captures found objects in the street and resituates them in gallery settings. Discarded items which may have been previously ignored get a sense of importance and given a purpose when displayed with significance in an exhibition.

His love of working with found objects became more interesting to me when Miller began explaining his lighting commission works. As a maker and love of the crafts, I am only too familiar with rummaging through charity shops for interesting materials. Collecting old lampshades from second-hand shops and fixing them together in a column seems like such a simple idea, yet Miller’s results are breathtaking. Illuminated from within and standing at over 8 metres, such a simple object becomes a masterpiece. Each of his lampshade structures are given double-barrelled lady’s names and are often sold to clients.

Miller stated that is work is not about him and is about what other people have made and how he loves to explore both machine and handmade marks on objects. It appears important to bring people into the gallery setting for Miller. In 2012, he wanted to bring the public celebration of the Royal street parties into the gallery and explained how in reality it wasn’t really a celebration of anything and more of an excuse to come together. Using his skills from his time as part of an installation crew, Miller set up a gallery space with rows upon rows of bunting hanging from the ceiling to bring the atmosphere into the expectedly calm setting.

Miller often works with other artists and friends and likes to develop work based on community interaction, documenting conversations between people. Through these relationships he has been able to gain commissions and meet people raise his profile. He explained how he takes photographs constantly and has a deep interest in what he sees around him, particularly cases of human intervention.

Miller described himself as the messenger and not the maker and was happy to admit that outside of his experience with woodwork, he does seek help with others materials. By creating functional work, Miller is able to provide a platform for others to make use of the piece and yet many of his images features objects that are failing to carry out their designated functions.