Jonathan Lynch did not begin his education studying art, as he states that his school did not perceive him as being artistically skilled, resulting in his connection with photography after he had left school aged 17.

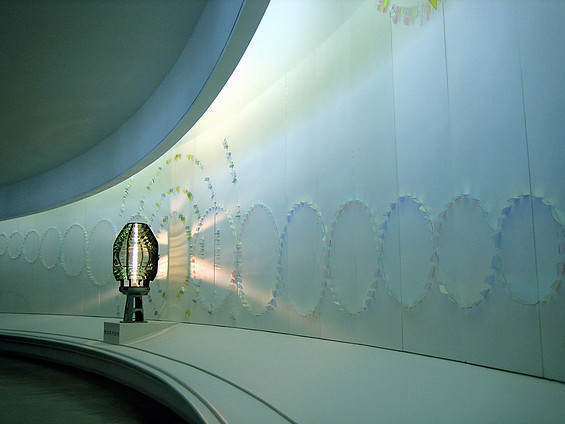

His main focus with his photography so far, has been to investigate and explore buildings with an aesthetic point of view. Lynch finds the process of taking photographs in new places very therapeutic and likes to visit these spaces to think and respond to the environment. He explained the significance of light in the areas and how it can reanimate the whole space. Lynch is interested in the history of the building and how simply being there can make you consider the people who once were there and their memories within the site. He likes to reflect upon the once lived-in rooms and how those people have moved on.

Lynch is fascinated by the idea that once people die, they are gone and how a picture can become precious. He explained that he only likes to take photographs of places when the light in perfect and that during the winter months the hue was the best. Yet he felt as though he did not have a real reason for taking these pictures and knew he needed to develop the meaning.

As the buildings no longer have a use or purpose, the surfaces never physically change and the lighting is the only inconsistency. After using a damaged camera, sections of his developed images were lost. This is when Lynch began experimenting with painting onto his photographs. This made himself and the viewer question the realness of the image and he was able to portray an image that was not true to the space.

Lynch has a passion for photography and explained how in the beginning it was important to his practice that his selected pictures were framed with care and attention, because he felt photography was about being beautiful and careful.

Through his visits to the spaces, Lynch became connected with the lost souls of the buildings and began to feel as though the light illuminated the absence. He began to collect old photos of people who had passed away from eBay, car boot sales and from friends and family. Lynch then began carefully cutting the people out of the photographs with a scalpel as well as removing them digitally, ensuring the shadows were left behind. This was when he realised that his title was beginning to make sense.

Through the extractions and enhancements of his images, Lynch liked to leave behind minor faults to leave clues that there was something missing, to provoke the truthful nature of the image. He discussed how through extracting the people from the photographs, light can then reactivate the characters.

Through a show in Edinburgh ‘Legacy’, he was able to produce two separate catalogues, one for his own photographs and another for his found ones. He explained how he saw these as separate chapters to the book of this idea.

Lynch seems a little unsure of what he wants to achieve and appears to have the luxury to take his time to decide what he requires from his artwork. When he began working for the Baltic Gallery in Gateshead, Lynch wanted to work with teenagers through youth projects to introduce his experiences to young artists. In 2011 when the gallery held the Turner Prize, Lynch worked with young people to respond to the works of the competition candidates. This is when he began discovering his love of teaching.

After some time away from studying he explained how he began to miss creating his own work and applied to do his Master’s Degree at the Royal College. Lynch then opened up about his personal dilemma with returning to studying and felt as though he was under pressure to be making art. As a result he turned down the offer to the Royal College and explained he did not feel ready to commit to the course. This is something I can relate to; having turned down offers myself in the past through not feeling like it was the right time in my life to return to education.

Lynch highlighted a need to explore and getaway after this event, which led to his move abroad to America to teach photography in Pennsylvania. He expressed his love of teaching and how pleased he was to have the experience of working in an educational environment, but how he soon felt like he needed to stop producing photographs for a while, so not to exhaust his ideas. Lynch then went on to talk about who he made a conscious decision not to make any more work for 4/5 years to focus on his educational work. He moved to Italy to continue this path and said he wanted to wait to develop his work because he was still unsure which way to take it.

Another year on, he returned back to the UK and moved to Newcastle to teach. At this point he stated he had made no new work since 2010, except for four rolls of film he had not developed from his time in America.

Lynch then restarted processing film and said he felt a sense of liberation when making prints without being so precious with the work. He decided not to think too much about the image itself and began embracing the mistakes. He was working in a school environment which was subject to error and learning and so incorporated the imperfect materials and damage. Lynch talked passionately about hoping to inspire his students to learn to use and love the dark room.

Finally he felt able to return to his work and began creating scenes for the extracted people from the old photographs. Lynch realised that the way people were positioned may have reminded him of things he had seen which were combining with his own memories, helping him to create characters for the scenes. This led to Lynch experimenting with his drawing abilities, where he created hand drawn scenes ensuring a gap was left for the missing people. This book of images was intended to have noticeable mistakes, where he could experiment with light through the removed figures.

Even though he wasn’t pleased with some of the outcomes of his processes, Lynch was eager to point out the importance of not denying any of your work, as it helps you to progress and learn.

Moving on in terms of materials, Lynch now wants to incorporate these images with clay and plaster, to experiment with destroying the picture. Through processing these photographs in plaster, the object itself is more fragile than it was and Lynch strives to get as much as he can from the images before they are gone. He hopes to recreate the existing picture through the emulsion left behind.

Lynch expressed a sense of regret for destroying the pictures, as it could be perceived as disrespectful. He was sure to highlight that his processes are not intended to be offensive and that he simply hopes to push the material to its limits. Lynch explained that he believes it can be a difficult process to look at images for some people and that there is a sense of irony that his current work won’t last longer than the original photograph.

Through is AA2A at the University of Sunderland, Lynch plans to work with imperfect materials, which is a huge leap from his original mind-set of precision and care. Using clay, he plans to experiment with pouring photo emulsion onto the unfired ceramic in the dark room to create sculptures of other people’s history. Lynch suggests that you must embrace your mistakes to help you to move forward.

It is apparent that Lynch is passionate about teaching and he was keen to express that he wants his students to see him as a working artist and not just a teacher. He believes that the work/life balance does not exist and they should not be separate from one other. Lynch explained that he used to think he could hide behind his pictures and now realises he can express himself through them and his processes. Unlike a lot of makers and artists, Lynch seems more focussed on making art for the materials and not for the industry.